I’ve recently started on the journey to get a private pilot’s license. One thing I’ve enjoyed about the process so far is the extent to which you’re encouraged to understand how most of the systems work at a fairly deep level. Contrast this to driving a car, where you can mostly get away with “turn key, use gas & brake pedals, don’t do anything stupid that would cause you to lose traction.”

Most trainer aircraft still in use were designed (and sometimes built) in the 1960s or ‘70s. So the systems are relatively primitive. For example, there is no onboard computer calculating the fuel mixture; you do that yourself. You have to know what a carburetor is and does. You need to know about the fuel system – where exactly it’s stored, the rate of fuel burn, how air temperature and fuel mixture and oil temperature impact engine performance. For more complicated aircraft, you need to become familiar with the manifold pressure system that uses a complicated oil-and-spring setup to control propeller pitch. This is all part of the fun and appeal of aviation, at least for me.

To oversimplify, turning on a plane like a Cessna 172 involves 3ish steps: turning on the master power switch for the airplane’s electrical system, turning on the power switch for the avionics systems, and turning on the plane’s magnetos. The first two are usually toggle switches, whereas the magnetos are a keyed switch, similar to a car’s ignition. You can roughly round your understanding of magnetos to “it’s basically the ’turn the engine on' switch”1, but I was curious and wanted to learn more.

What are magnetos? Magnetos are a self-contained electrical system for powering the plane’s spark plugs, which use the mechanical power of the running engine to produce enough voltage to keep the spark plugs sparking, independent of the aircraft’s battery. They’re called magnetos because they use permanent magnets rotating past wire coils to generate electrical current.2

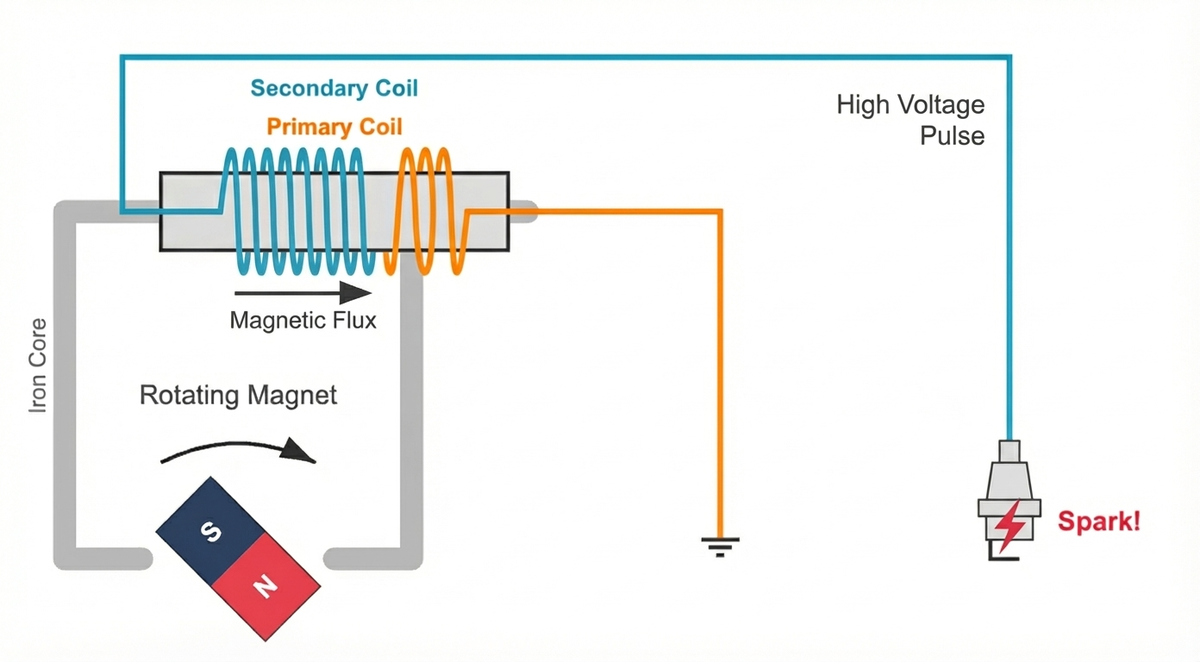

Crudely drawn, likely not fully accurate magneto diagram

Spark plugs need a reasonably high voltage (usually >10kV) to ionize the air to create a spark. To achieve this high voltage, they have two coils – a primary and a secondary – which work similarly to a step-up transformer.

To generate the high voltage needed to produce a spark, a mechanism connected to the engine timing system periodically disconnects the primary coil, collapsing its magnetic field. This field collapse induces a higher voltage in the secondary coil, using Faraday’s law of induction.3

Why magnetos? On essentially all modern internal combustion engines for cars, the spark system is powered by the internal battery, which in turn is charged by the alternator – an electric generator which runs off the mechanical energy generated by the running engine.

Aircraft engines also have an alternator and battery system – for powering aircraft electronics like avionics and lights. Why not use those for the engine spark plugs too? Primarily for isolation. Modern electronic ignitions are coupled to the electrical system. If you have an electrical fire in the cockpit, the first step is to turn off the master switch, cutting off all power to the plane. If your engine relied on that power for its spark plugs, it would also stop.

Magnetos are mechanically coupled to the engine and propeller. As long as the propeller continues to spin, the magnetos will continue to provide the energy needed to keep firing, completely decoupled from the rest of the plane’s electronics.

Losing your lights and avionics if your battery or alternator fails is a manageable emergency, but losing your engine is potentially catastrophic. The total isolation of the electronics and engine systems makes a coupled failure less likely.

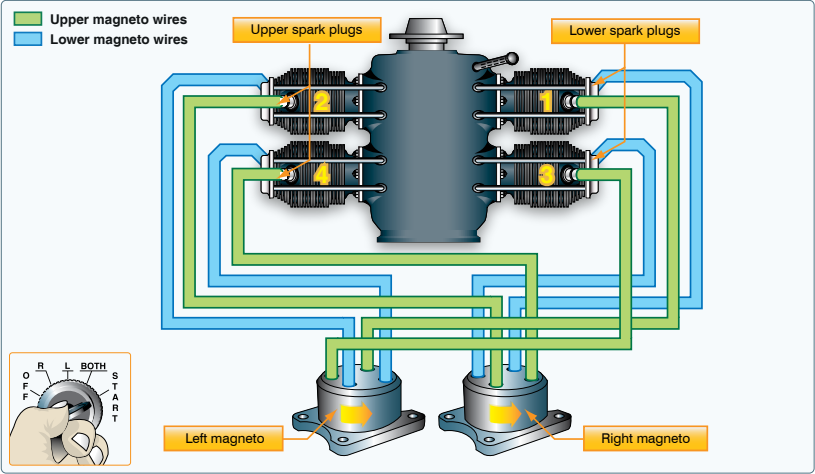

Left and right magnetos: Many engines have two sets of magnetos – labeled “left” and “right” – with an option to have both enabled. The “both” setting is what the plane usually operates with. Switching off one set of magnetos noticeably decreases the RPM of the running engine. Why? Naively one might think that half the engine cylinders (e.g. the “left half”) use each set of magnetos. This is not the case; rather, each set of magnetos is wired to each cylinder. Cylinders have two spark plugs each connected to one of the two independent magneto system.

Aircraft magneto system schematicSource: Pilot Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge

Why two sets of magnetos? Well, mostly for redundancy again. The engine can still function quite well4 even if one of the two magneto systems is inoperative. But there’s another reason: Recall how I mentioned earlier that only enabling one set of magnetos reduces engine RPM, all else equal. Why? Having two spark plugs in each cylinder improves the engine’s combustion by starting the combustion at two places simultaneously, reducing the amount of time the flame takes to expand through the cylinder. This also makes the burn happen more evenly, to reduce uneven strain across the cylinder surface.

Further reading: How It Works: Magneto (AOPA)

-

Technically, magnetos aren’t even really “turned on” since they’re passive systems. Turning the switch from OFF to ON un-grounds the magnetos. When OFF, the magneto coils are grounded to the airframe body, which prevents them from generating electricity. Actually turning on the engine still requires the battery to power a starter motor. ↩︎

-

Magnetos are a form of alternator that uses permanent magnets as the source of the magnetic field used to generate current. Non-magneto alternators, on the other hand, use an electromagnet as their magnetic field source. This has the side effect that if your battery is dead, the alternator can’t function, since there isn’t an initial “excitation” energy to energize the coil, creating the field that then drives current. ↩︎

-

The ratio of the number of turns in each of the primary and secondary coils determines how much the voltage is stepped up. To act as a step-up transformer, the secondary coil has many more turns of wire than the primary coil. ↩︎

-

In flight, that is. You can safely return to the ground easily with just one magneto. You definitely wouldn’t want to take off with only one. ↩︎