1.

One of the common criticisms of modern AI systems is that they aren’t sufficiently embodied. The idea being there’s some inherent quality of being an agent embedded inside a body in the physical world which cannot be attained by a token-predicting LLM, regardless of how intelligent an agent becomes.

To address the validity of this criticism, we need to have a philosophically rich understanding of what embodiment is and what it gets us in terms of cognitive capacities.

2. The Four E’s

The best framework I’ve yet found for understanding the benefits of embodiment for cognition is “4E cognition”. The four E’s here being: embodied, embedded, extended, and enactive.

Embodied cognition, our principal concern, is the notion that the body in which an agent is embedded is deeply tied to the cognitive processes that the agent can support. It’s the opposite of “brain in a vat”; the body constrains and guides the concepts that a brain can conceive. The fact that colors, material properties, and the rest of the pieces of our inner mental worlds “exist” is guided by the sensorial situation we’ve found ourselves in – having eyes to perceive colors, sense organs to feel texture, and so on. Furthermore, our conceptual handles for things like doors, chairs, water glasses, and so on are constrained by how we engage with the physical world. In this view, “chair” is not a natural category in the “out there” world; it is contingent on our embodiment.

Embedded cognition is cognition that is aided by being situated in a surrounding environment that supports the cognitive tasks. This is specifically referring to environmental affordances which support the cognitive process, which are still happening in the brain. For example, tool use – using an abacus to support a math operation, or using a book shelf to sort books, are examples wherein an agent’s cognitive load is reduced by being embedded into a suitable environment.

Extended cognition suggests that aspects of your environment, outside your brain, are not just supporting your cognition but is actually a constituent part of the cognitive process. An example of this is using a notebook or smartphone as an aid to memory and focus.

Enactive cognition is the idea that cognition “emerges from sensorimotor activity” – that there exists no bright line between premeditation and action.

3. Perception and Embodiment

Going deeper on the embodiment critique, I think it becomes useful to look at the interaction between agent and environment: perception. The central argument of embodied cognition is that the interaction between environment and cognition is somehow essential for getting the type of thinking that humans are capable of.

From David Chapman and Jake Orthwein’s recent wide-ranging discussion, we get the following view of perception:

The reason why 4E-type things are part of the solution to [the problem of perceptual relevance] is that you sort of evolve to construe the world in certain narrow ways that have to do with the kind of thing that you are. You don’t encounter the world as it is first and then have to select from among that – the world presents itself to you in terms of the kind of being that you are. And that automatically narrows the frame of perception dramatically.

(Emphasis mine)

This is a fairly radical claim. The intuitive view of perception is that there is a world “out there” and that we are perceiving that world in our minds in a way that reflects how the world actually is – with the implied corollary that any creature would see the world roughly the same way as us.

But this idea flips that intuition. From the infinite ways that sense organs could make an internal map of the exterior world territory, the maps that we tend towards making are the ones that are selected by the type of being that one is. Creatures that can walk will see doors as “walk-through-able” in a way that water-bound creatures would not.

Our ability to resolve raw sense data into well-defined objects, intuitively and preconsciously, is not because those objects exist in the world in some objective sense, but because we’re the type of creature that finds use in, for example, being able to distinguish between objects that are likely dangerous or safe. The categories that feel “natural” to us are natural only relative to our particular form of embodiment, a pure circumstantial contingency.

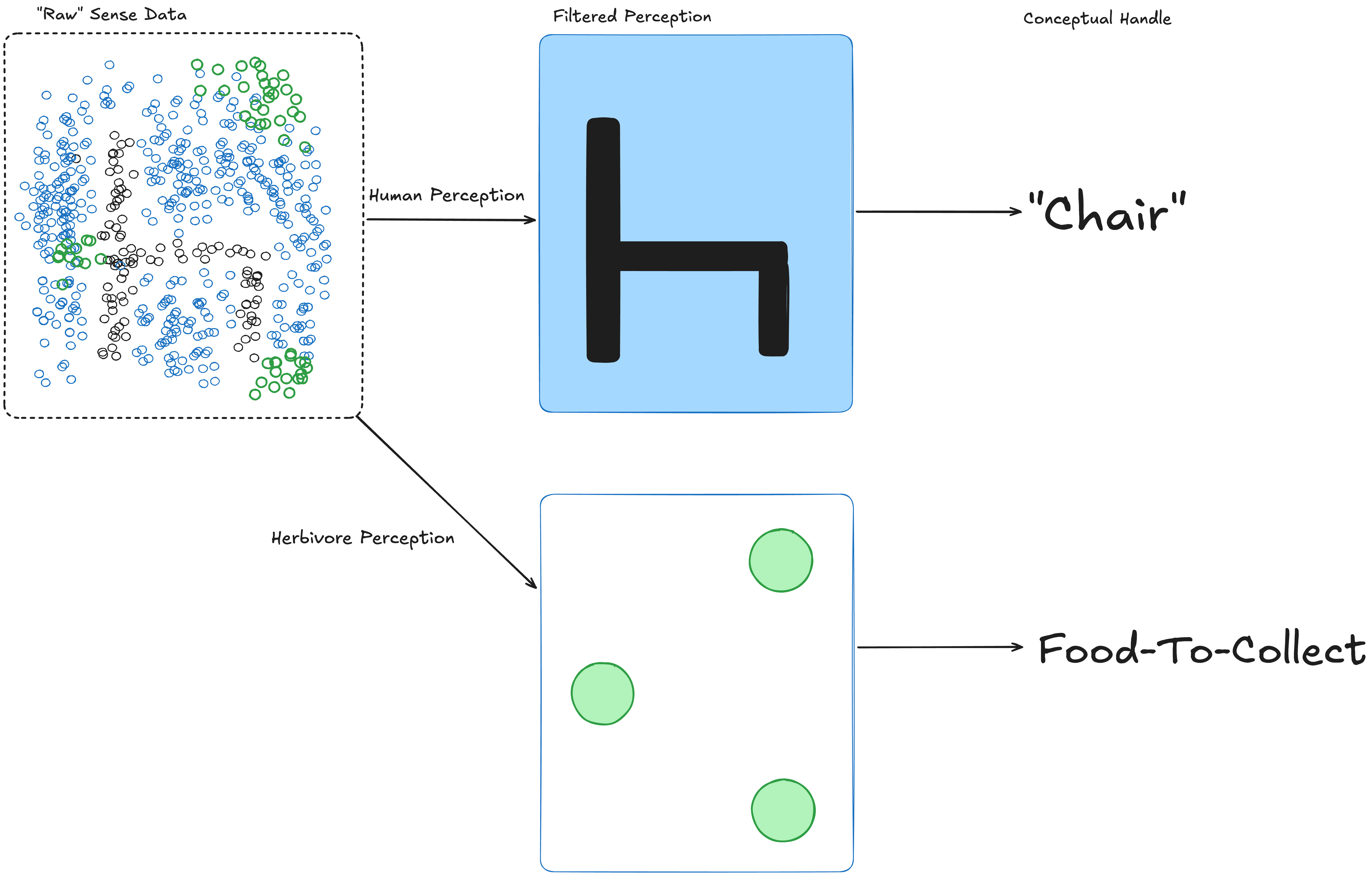

Perception filtering

This figure crudely illustrates the process of perception filtering. There exists some sense data “out there”, and depending on the type of being, that sense data is filtered into a different set of concepts. The human resolves the outlines of the black object against the blue background as a “chair”, whereas a hypothetical aquatic herbivore evolved to use its visual sense data to search for food resolves the green patches and attaches the concept of “food” to them. Same sense data, different resolved concepts.

Orthwein continues:

And then perception is being narrowed still further by your goals, your motivations, what sorts of states are active in you, and the actual embodied situation that you find yourself in each moment. So you’re never doing this rationalist view from nowhere from which you have to deduce what’s relevant. The world is giving you a relevance moment by moment by moment, which is the Heidegger “always already meaningful” picture.

This is the second level of filtering. It’s not just “what can you perceive given your contingent embodiment”, but it’s also “as an agent with goals and motivations, certain things will be more or less salient, preconsciously”. The key piece for me, here, is the notion that inside our heads we’re never actually doing the rationalist “view from nowhere” stance. We can try to approximate this with deliberative thinking, but this is only ever a mere approximation. Embodiment affords and demands a level of perception-based filtering.1

4. Mapping the 4E’s to LLMs

OK, so I’ll admit this has become a bit abstract. Let’s rein this in by trying to map these concepts onto extant LLMs.

Going in reverse in the 4Es:

- Are agents enactive? Unclear. Sufficiently harnessed AI agents can “take action” (heavy scare quotes intended) in the world, but it’s not clear how serious we should take this. A thermostat is “enactive” in the world, in that it’s able to control its environment through action, and the environment in a sense allows it to “enact” its cognition. If we grant this property for thermostats, we should likely grant it for AI agents as well, but this doesn’t seem to prove much.

- Are agents extended? Definitely, yes. Claude Code’s uses TODOs essentially the same way a human would. Models have limited memory in their context window. Reading/writing from a scratch pad, or using a code-interpreter to offload complicated math seems like “extended” cognition in a very similar way to human extended cognition.

- Are agents embedded? I’d say this is a lukewarm “maybe”. We scaffold LLMs into “agents” specifically by putting them into harnesses which allow them to interact with the world. However, the cognition itself isn’t embedded in the environment. There is still a clear line to be drawn between “what is LLM” and “what is environment”.

- Are agents embodied? I’d written up to this point having in my mind a clear “no”. I still think the answer is pretty firmly “no” for most reasonable definitions of “embodied”, but I’m less certain than I used to be. Certainly, certainly, I’m not making the claim that AI agents have any form of physical embodiment. This is just obviously false. And the extent to which we slap an LLM onto a robot and call it embodied – I think that’s cool, but architecturally still distinct from what 4E is calling embodied.

What’s still bringing me back to a firm “no” on the embodiment question, setting aside common sense, is the notion that “constitution” is an important theme of true embodied cognition:

Constitution: The body (and, perhaps, parts of the world) does more than merely contribute causally to cognitive processes: it plays a constitutive role in cognition, literally as a part of a cognitive system. Thus, cognitive systems consist in more than just the nervous system and sensory organs. (Source)

This just does not seem to be true of LLMs. Scaffolded AI agents have “senses” in that they can be told about things happening in the world, and they can even request measurements to be taken of the world on their behalf, but they are not of the world. Everything is still just tokens to them. Even multimodal visual information is still provided in the same learned representational space of tokens. There is no sense in which they have sense perception of the world, or parts of their cognition which are causally of the world, such that one could say that their cognition is actually embedded in the world.

5. The Tokenverse

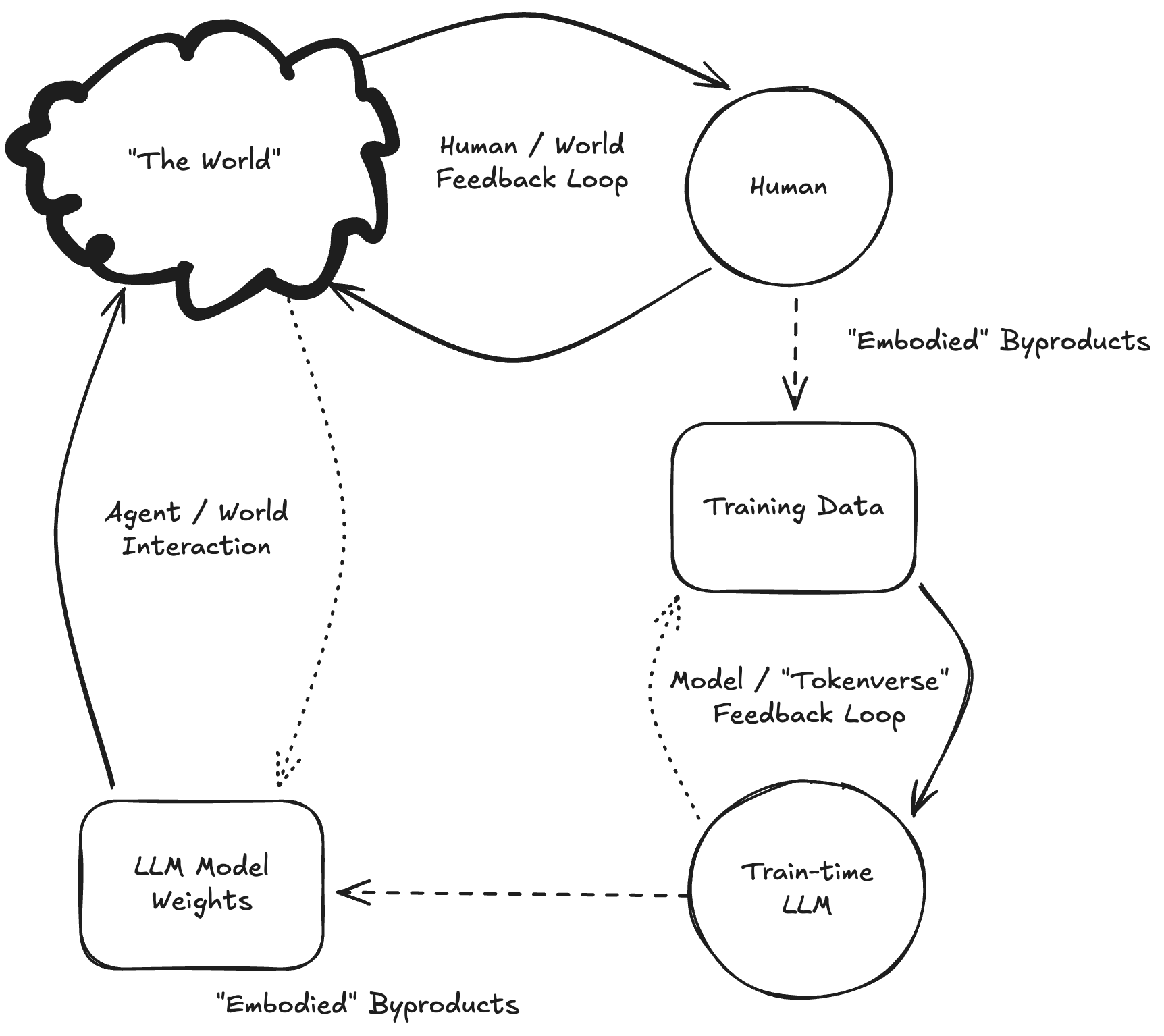

A common critique of the field of AI alignment is the provocative question “Aligned to what?” I think there’s a natural analogy here: “Embodied in what?” If we grant LLMs some primitive form of embodiment, they seem to be embodied in something like a “tokenverse”, a linguistic ecosystem, not the physical world.2

Agents acting in this “tokenverse” still seem to be quite capable of taking action in our real physical world – albeit in ways that we’ve constructed to mediate these actions.

So what does this mean for the criticism that “AI systems are insufficiently embodied”? I think insofar as this criticism is trying to say that “AI cognition is different from human cognition”, that is just obviously true. However, this does give us a useful handle on how these two forms of cognition are different.3

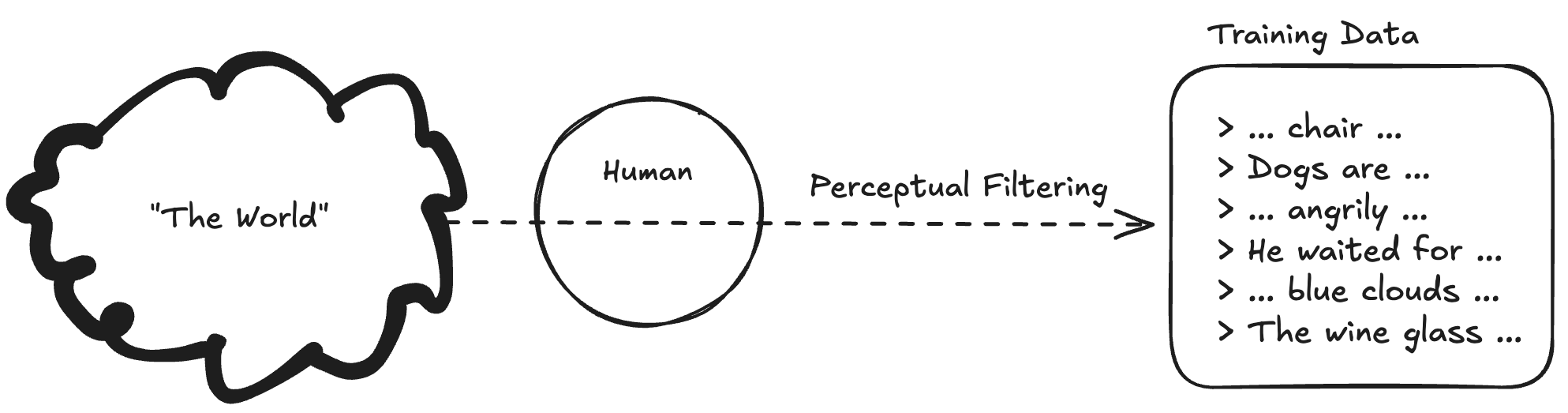

Our embodied perception filtered “the world” into concepts. Those concepts ricocheted off billions of human minds, eventually crystallizing in the internet datasets that became the basis for LLM training data.

Now LLMs use these human-derived concepts in their abstract “tokenverse” to take actions that impact our physical world. Perhaps this is why “alignment by default” seems to be actually going fairly well so far? Naively, it would seem much easier to “align” something which already shares a reasonably close set of conceptual handles to us.

LLMs didn’t have to learn how to interact with the world and form their own conceptual handles based on their weird alien understanding of what it means to exist in the universe, they were able to learn these from statistical patterns in tokenized concepts from human-derived data.

Now we have full loop. Human experience is distilled into concepts represented as statistical patterns in the training data, a “byproduct” of embodied experience. LLMs train against this data and learn statistical patterns, but can’t influence the training data – its “tokenverse” – in the same way that humans can influence the world through their own physical embodiment as part of their feedback loop. Similarly, when LLMs take actions in the world, they are doing so in a way that is constrained by the concepts in their “tokenverse” rather than the world itself. At present, LLMs are also limited in their ability to be influenced by the world itself, as they are mediated by a set of static model weights which aren’t themselves influenced by the world during interaction.

If we take the “tokenverse” idea seriously, we should consider what is implied by being “embodied” within it. LLMs clearly develop some internal conceptual landscape that produces their resulting outputs. Empirical investigation into model features supports this. It would be quite surprising if the learned concepts mapped 1:1 onto human concepts. This would imply that the conceptual landscape that best withstands the optimization pressures of model training maps with high fidelity directly to human filtered concepts, which would be a quite strong claim. More likely, LLMs develop an internal conceptual landscape that approximates human concepts, but is itself quite foreign. Indeed, empirically this appears to be pragmatically indecipherable.

For now, if LLMs are embodied of anything, they are embodied of the texts and concepts we first perceived via our own physical embodiment.

Cover: Barcelona, Spain

-

I’m going to have to read more about Heidegger’s notions of “pre-ontological” existence now, I suppose. ↩︎

-

As an aside, I don’t think there’s any spooky going on with respect to tokenization in particular. That is, if LLMs eventually transition to using byte-level tokens, I don’t think that changes the fundamental argument. ↩︎

-

Here, we are implicitly granting that AI cognition is cognition. I’m not 100% sure we should be ready to bite that bullet, but that’s a topic for another time. ↩︎