1.

It’s hard not to think about the direction the software engineering field is going in. I don’t think you, dear reader, need to be reminded of this, but just to set up some timeline tentpoles:

- In mid 2024, Github Copilot was something of a pleasant convenience for coding. This was the “fancy autocomplete” era. A “nice to have”, which you could lean on, but where you still felt fully in-control of the process of writing code.

- In early February (2025), I wrote about how I was having more success with Cursor (still great) and Copilot Edits (largely left in the dust). I distinctly remember writing greenfield code with the Cursor Composer in late 2024, being quite impressed, but still finding that the frontier models of the time would fall over after a project got much past 1-2k lines of code.

- Weeks after I wrote that, the initial version of Claude Code was released. Codex (in April) and Gemini CLI (in June) followed soon after. Claude Code was a step change improvement. It “just worked”. You told Claude what to code, and it largely could just do that.

- Claude Sonnet 4.5, released September 29, and Claude Opus 4.5, released November 24, somehow both felt like breakthroughs in coding ability.1 Codex CLI has improved through the year as well. I still find Claude Code to be the “best” of the CLIs, but Codex is still quite competitive. Cursor remains competitive as well.

In late 2024, I remember having a bit of the feeling of being “the weird one” at work, who tried to offload as much of my coding on LLMs as possible. I developed a bit of a reputation for this, and throughout 2025 I’d have people spontaneously ask me in 1:1s if I’d found any new techniques or tips for getting better performance out of AI coding tools.

These tools are excellent. They’re also, descriptively, somewhat of an inevitability. The tools exist, they are getting better month-over-month, there are market forces pushing for their adoption, for the time being there is immense comparative advantage in being able to wield them effectively; ignoring them seems increasingly unwise.

Throughout 2025, I felt more and more that I was able to offload much of the implementation of my work to coding agents. I’m a Tech Lead, so my time is split between meetings, more meetings, writing docs, and preciously guarded IC time. Offloading more to coding agents increased my effective output, as I could fire off an agent (or 2, or 3) before a meeting, check their work afterwards, and guide them towards solutions over the course of my day.

This wasn’t “merely” greenfield work, either. Much of this was changes to old, complex, mission critical codebases. I reviewed the output with an appropriate amount of rigor, and became increasingly impressed.

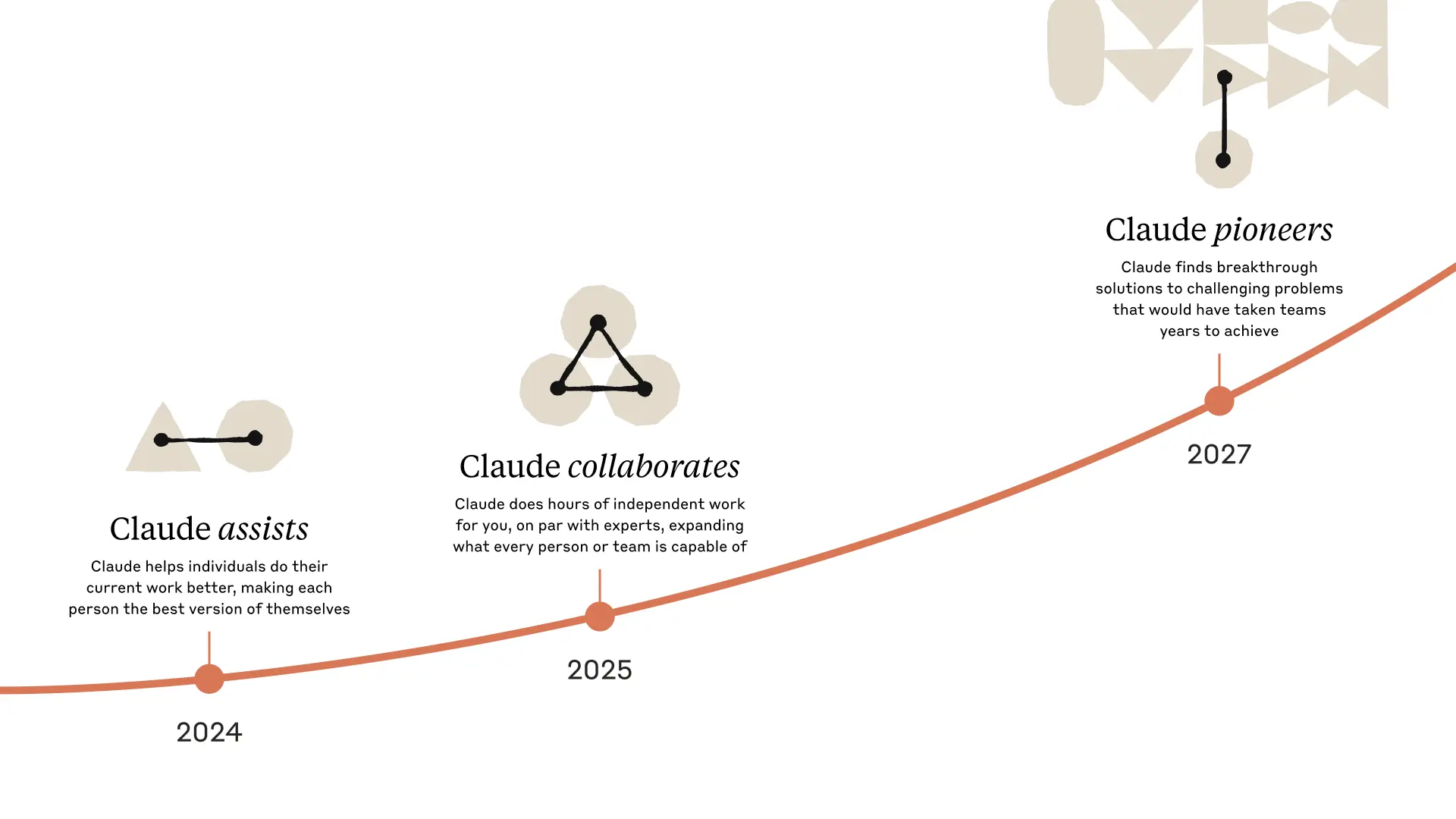

Look, I don’t want to sound like I’m an Anthropic marketer, but if you look at this “”chart”” from the February 24 release of Claude Sonnet 3.7 and Claude Code, I think they landed their roadmap for this year.

Claude Code release ’timeline’ chartSource

Claude Code – the others too, but in particular CC for me – feels and acts like a collaborator at this point. In the first half of the year, it felt like a reasonably competent intern; in the latter half, it’s a jagged-but-staggeringly competent junior engineer who you can sometimes coach into writing legitimately inspired code with a simple “but how would a senior engineer refactor this for modularity and maintainability?”

All that to say: with the release of Opus 4.5, I sense a shift. I find no pleasure in saying this. Most of what we call coding is now “solved”. I don’t think, however, that we’re post “software engineer”. I don’t think we are in any way “post-software”. I expect the amount of software being written to dramatically increase as the cost to produce it falls. I also believe that we will still need deeply technical people to guide that production, and develop and maintain the infrastructure to run it.

And yet: We are nearly at coder-equivalency for economically useful coding. A sufficiently experienced software engineer can now write >90% of production-ready code purely through prompting. You still largely need to know what to prompt, but even that becomes easier as models’ intuitions for software development improve.

I was admittedly skeptical at Dario Amodei’s March 2025 claim that this would happen within the year; it happened a few months later than his timeline, but in my opinion it did happen. The obvious corollary is that, for now, that remaining 10% becomes extremely valuable.

The industry, collectively, has had less than a year to respond to this. Regardless of what various leadership-class people say, this is not yet priced in. It’s not priced in to e.g. CS university program structure, engineering ladders, company structure, team structure, and so on.

To think through what may remain, I’ll attempt to defer to history.

2. Drafters: A Historical Analogy

There’s an analogy that’s been bouncing around in my head as I’ve been processing what appears to be this upcoming shift in software production. It goes something like this: in the mid-1900s, drafters – those who would literally draft engineering diagrams for architects, civil engineers, electrical engineers, mechanical engineers, and so on, were in relatively high demand. As were human computers.

‘Man Sitting at Drafting Board’, circa 1936Source

Automation came for these fields. CAD, and AutoCAD in particular in the early 1980s, automated much of engineering drafting. Not all, but a lot of it. Automated circuit design via Electronic Design Automation automated much of the manual work done to create PCBs. And, of course, human computers, well… yeah.

I tried getting actual labor statistics for this. For the time period I most cared about (between 1940 and 2000), the data online was spotty for the amount of effort I was willing to put into this.2

In any case, this seems like a compelling analog for one future of software engineering. Drafters were a distinct role, separate from e.g. a mechanical engineer or structural engineer. Software “engineering” has a bit of both; it encompasses design, production (coding), and maintenance (DevOps, woo…).

CAD and EDA didn’t destroy drafting and related technical-but-not-engineering roles. CAD technician jobs still exist today, but it’s a more commoditized skill than “pure” engineering. If this analogy holds, then the parts of the software engineering world that looked more like “software drafters” than “deep-in-the-design engineers” will largely be commoditized and will shrink.

Drafter, 1992Source

It’s unclear what chunk of the existing SWE ecosystem is drafters. I think most people that get into SWE for enjoyment of the field probably aren’t in this category, but it’s definitely out there.

3. What Remains

If I was able to offload all my coding work on an AI, there still does seem like a lot left to do as a software engineer. Great! I don’t have to code anymore. Ah, wait – still have to figure out how to get all the infrastructure running to build out my new project, keep the lights on for the dozens of components we already have in flight, reason through observability, debug wicked weirdness that happens past the 99th percentile tails, review my agents’ and my coworkers’ code, write designs, review designs, give career coaching, and on and on.

Coding also isn’t completely “solved” yet either! I may not be in the mud writing thousands of lines of code, but I do still exert significant editorial control over everything that gets checked-in.

AI helps with a lot of this. I feel like I have a lot more leverage than I had a year or two ago, but we’re still pretty far from closing the loop entirely. AI-assisted debugging, great! AI-assisted responses in the internal help channel for what my team owns, great! AI-assisted first passes at design docs I’ve written, great! AI-assisted code review, great!

I notice that my work days still contain many hours, I still remain busy, much work remains to be done. Infrastructure remains hard. If anything, all this has just allowed us to do more and be more ambitious. Systems rely on momentum and inertia in part because it requires a ton of time and effort to evolve a complex system. Reducing the time to build new systems or evolve old ones is legitimately helpful, but human-used systems still operate on human-driven time scales – for now.

At all the companies I’ve worked with, “produces high quality code artifacts” was always a bullet point on the SWE ladder, but it was but one of a dozen other skills and responsibilities that come along with the role. In the immediate future, I don’t see this expectation going away. In the medium term, I could see this transitioning away from a focus on artifacts, to a focus on impact – as was already the expectation for more senior engineers.

I predict agency & impact will become more of an expectation for junior engineers, since the tools for helping yourself have become so powerful.

What remains true:

- Knowing how code works at a gears-level is still largely valuable.

- Foundational computer science knowledge is still largely valuable.

- Software “taste” or discernment or heuristics is still largely valuable.

What is probably not true:

- Being solely a “coder” is a path to stable employment.

- Being a software “craftsperson” ceases to be valuable or enjoyable. (Rather, I think the value will likely shift and look more like an actual craft – high end, not commoditized, but not mass market.)

There is a lot going on in AI as we end 2025. I have grown to dislike the phrase “these are the worst the models will ever be” because I feel like it tries to prove too much and has been co-opted as marketing. But adopt that frame for a minute and project a year or two forward to where things could go. What skills remain valuable? What deep knowledge do you still need to draw upon to know if you’re being BS’d by a confused coding agent? What can you learn now, build now (experientially!), given that the cost to churn out new quality code is falling to zero? What cognitive work can you reinvest your time in, if coding demands less of your work day? What types of people are going to be good leaders in times of industry change, like these? What type of organization do you want to invest your career capital in?

Cover: Wikimedia

Obligatory: These are my own opinions and do not reflect those of my employer, etc.

-

They seemed to me like breakthroughs in non-coding abilities as well, which is legitimately impressive as neither of them is specialized as a coding model. ↩︎

-

Epistemic status: Vibe check. One source put the number of drafters in 1940 at 111k, up from 98k in 1930 and 66k in 1920. Confusingly, this BLS paper seems to only indicate there were ~55k drafters in 1990 (though their counting mechanism is unclear). This St. Louis Fed report indicates 200k drafters in 2000 and 193k in 2023. To make meaningful comparisons, we’d have to correct for population growth, definitional shift, and so on. Squinting at the numbers, it seems like post-2000 there has been a slight decline in drafting employment, definitely compared to the rest of the economy. ↩︎