The thing that separates life from non-life is information. - Paul Davies

I’ve probably learned about the thought experiment of Maxwell’s demon at least half a dozen times – in multiple physics courses, in multiple books. Until I read Paul Davies’ The Demon in the Machine, I don’t think I realized that the paradox of Maxwell’s demon had actually been solved.1 More on that later.

The core thrust of Paul Davies’ The Demon in the Machine is to look at life as a puzzle of thermodynamics and information. It starts with the question: how is it possible that life seems to reliably be able to render order from chaos? Looking at living systems, they are able to hold boundaries. Life is able to create and sustain fantastically ordered structures – cells, organs, limbs, brains – out of the chaotic inorganic soup comprising the rest of the physical universe.

Davies’ answer is information theory, with his core thesis that “Life = Matter + Information”.

1. Demonology

The titular “demons” of Demon in the Machine are, of course, those of the Maxwell Demon thought experiment. Maxwell’s demon – sorry, now you have to listen to yet one more explanation of it – is the thought experiment wherein a gas is split into two chambers, separated by a frictionless door. A demon watching molecules of gas transiting between the two section could use the door as a sort of filter – blocking slow particles from moving to, say, the left section, resulting in more slow particles being in the right section and more fast particles being in the left section.

This violates the Second Law of Thermodynamics, by reducing the amount of entropy (“disorder”) in the system. As another intuition for this, we effectively “sorted” a gas at equilibrium into hot and cold without using any energy.

Things get weirder: were this true, we could configure this demon to, instead of merely sorting the particles using its door, run an engine to produce work. We reconfigure the room to have the door also act as a piston. When we’ve sorted more hot particles into one side, we can close the door and have it move as a piston would, the hotter particles pushing against the area with less pressure, expanding until thermal equilibrium is reached. Then, the door can be reopened and the process repeated. This demonic engine is known as a Szilard engine.

Were Maxwell’s demon possible and costless, we could (say) run a refrigerator indefinitely, without any energy input. Were Szilard engine possible and costless, we could (say) extract an vast amount of mechanical energy from a gas at thermodynamic equilibrium.

2. Information Engines

The bad news is that such a costless engine is not possible. The good news is that Szilard engines are actually realizable in the physical world.

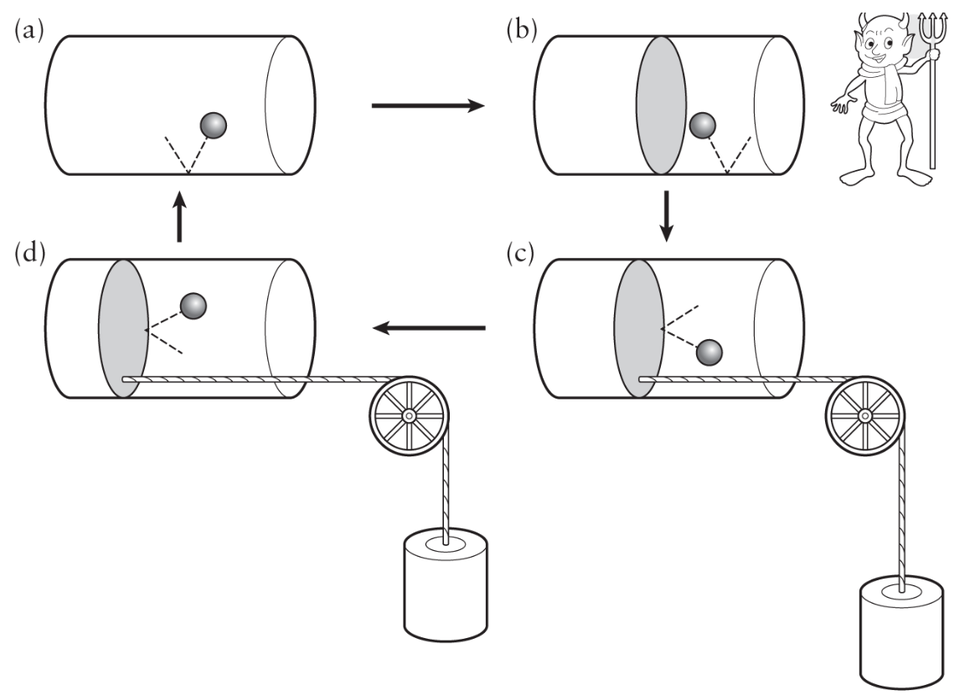

Leo Szilard, working in 1929, actually suggested a more simplified version of the Maxwell Demon thought experiment to power his engine than what I sketched above:

- We simplify the setup to a single molecule in a box.

- The demon can insert a partition in the middle of the box, such that the molecule is trapped on either the left or right side of the partition.

- The demon knows the location of the molecule – whether it is on the left or right side. This is 1 bit of information.

- The demon can position the piston on the side where the molecule isn’t, so the molecule pushes against it and does work.

Szilard’s engine; Figure 4 from The Demon in the Machine

Szilard suggested that the energetic “fuel” for this engine was the knowledge of the molecule’s location.

Szilard concluded, reasonably enough, that the price [of the engine’s work] was the cost of measurement.

As it turned out, this was a mistaken conclusion. IBM physicist Rolf Landauer extended Szilard’s work in 1961, introducing “Landauer’s Principle”, which states that it is not the measurement of information that requires work, but rather the erasure of information. Landauer was attempting to quantify the minimum amount of work to operate a logic gate, in studying the physics of computation.

Landauer coined a now-famous dictum: ‘Information is physical!’ What he meant by this is that all information must be tied to physical objects: it doesn’t float free in the ether.

This is fairly unintuitive, so let’s hold on this point for a minute: measuring and accumulating information is thermodynamically free, but erasing that information is costly.

As an intuition, we can look at the notion of “reversibility”. I map this in my head to something like: while measurement and accumulation of information is happening, we are traveling down a thermodynamic gradient. Yes, we are “getting work”, but in doing so we are traversing the thermodynamic state space of the world. Each time the Szilard engine demon makes a “left or right” decision, there is an implicit ledger of “lefts” and “rights” that is collected alongside the work coming out of the system. The thought experiment abstracts this ledger, but it is in fact a physical configuration in the Demon’s memory (weird, right?).

This ledger breaks down, eventually. When you want to reuse the Szilard engine, you have to eventually reset it, as the Demon does not have infinite memory. And that erasure is when the process becomes irreversible. With the ledger in hand, you can trace back the full state space tree of the engine operation. Deleting the ledger resets your memory back to baseline, but also makes it such that you cannot trace back the operation, going from an in principle reversible process to an irreversible one. This is the energetic cost of computation.

3. Physical Demon Instantiation

We have gotten slightly closer to an understanding of the physical instantiation of a Maxwell demon / Szilard engine, but the intuition of the thought experiment breaks down when we consider the ledger. Why do we care about the demon’s memory? To see why, Davies has us remove the “magic” animation of the demon and instead try to instantiate this idea in a physical system.

I will quote liberally here, because I find this explanation by Davies, though long and challenging to visualize, to be one of the most fascinating insights from the book:

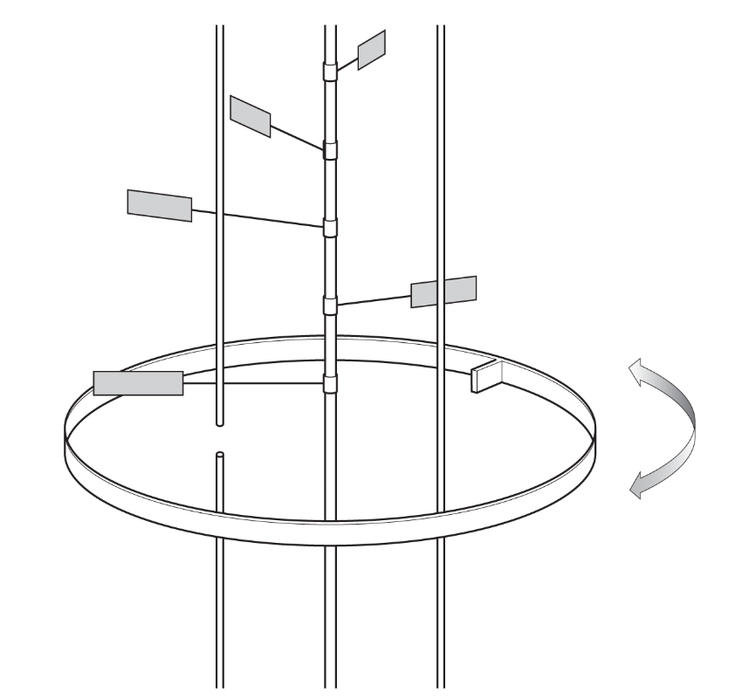

It must be possible to substitute a mindless gadget – a demonic automaton – that would serve the same function. Recently, Christopher Jarzynski at the University of Maryland and two colleagues dreamed up such a gadget, which they call an information engine. Here is its job description: ‘it systematically withdraws energy from a single thermal reservoir and delivers that energy to lift a mass against gravity while writing information to a memory register’. …

The Jarzynski contraption resembles a child’s plaything (see Fig. 6). The demon itself is simply a ring that can rotate in the horizontal plane. A vertical rod is aligned with the axis of the ring, and attached to the rod are paddles perpendicular to the rod which stick out at different angles, like a mobile, and can swivel frictionlessly on the rod. The precise angles don’t matter; the important thing is whether they are on the near side or the far side of the three co-planar rods as shown. On the far side, they represent 0; on the near side, they represent 1. These paddles serve as the demon’s memory, which is just a string of digits such as 01001010111010 … The entire gadget is immersed in a bath of heat so the paddles randomly swivel this way and that as a result of the thermal agitation. However, the paddles cannot swivel so far as to flip 0s into 1s or vice versa, because the two outer vertical rods block the way. The show begins with all the blades above the ring set to 0, that is, positioned somewhere on the far side as depicted in the figure; this is the ‘blank input memory’ (the demon is brainwashed). … One of the vertical rods has a gap in it at the level of the ring, so now as each blade passes through the ring it is momentarily free to swivel through 360 degrees. As a result, each descending 0 has a chance of turning into a 1.

Jarzynski’s information engine; Figure 6 from The Demon in the Machine

Now for the crucial part. For the memory to be of any use to the demon, the descending blades need to somehow interact with it (remember that, in this case, the demon is the ring) or the demon cannot access its memory. … The demonic ring comes with a blade of its own which projects inwards and is fixed to the ring; if one of the slowly descending paddles swivels around in the right direction its blade will clonk the projecting ring blade, causing the ring to rotate in the same direction. The ring can be propelled either way but, due to the asymmetric configuration of the gap, there are more blows sending the ring anticlockwise than clockwise (as viewed from above). As a result, the random thermal motions are converted into a cumulative rotation in one direction only. Such progressive rotation could be used in the now familiar manner to perform useful work. …

So what happened to the second law of thermodynamics? We seem once more to be getting order out of chaos, directed motion from randomness, heat turning into work. To comply with the second law, entropy has to be generated somewhere, and it is: in the memory. Translated into descending blade configurations, some 0s become 1s, and some 0s stay 0s. The record of this action is preserved below the ring, where the two blocking rods lock in the descending state of the paddles by preventing any further swivelling between 0 and 1. The upshot is that Jarzynski’s device converts a simple ordered input state 000000000000000 … into a complex, disordered (indeed random) output state, such as 100010111010010 … Because a string of straight 0s contains no information, whereas a sequence of 1s and 0s is information rich, the demon has succeeded in turning heat into work (by raising the weight) and accumulating information in its memory. The greater the storage capacity of the incoming information stream, the larger the mass the demon can hoist against gravity.

(Emphasis mine)

I’d suggest watching this YouTube video to get a better sense of how this works.

So now we have it: a system extracting mechanical energy from a gas at thermodynamic equilibrium by means of recording information. Here we see the physical manifestation of the demon’s memory. There are a finite number of paddles our engine has. When we run out, we cannot use the engine anymore. And in this physical system it becomes clearer that in order to use the engine indefinitely, we need to reset the system back to its “blank slate” state after having used up its ledger space.

Having established this, the remainder of The Demon in the Machine discusses the connection between information theory and biological life.

4. Life and Information

Much of Davies’ arguments for the relationship between life, matter, and information boil down to two main ideas: the notion that biological systems have an informational “software” that run on top of the bio-mechano-physical “hardware”, and that this informational “software” has top-down causal power.

To the first point, about biological “software”:

Biological information is more than a soup of bits suffusing the material contents of cells and animating it; that would amount to little more than vitalism. Rather, the patterns of information control and organize the chemical activity in the same manner that a program controls the operation of a computer. Thus, buried inside the ferment of complex chemistry is a web of logical operations. Biological information is the software of life.

To the second point, on the top-down causal power of information:

Counter to most reductionist thinking, the macroscopic states of a physical system (such as the psychological state of an agent) that ignore the small-scale internal specifics can actually have greater causal power than a more detailed, fine-grained description of the system, a result summed up by the dictum: ‘macro can beat micro’.

This notion of top-down causality amounts to a firm rejection of “strong reductionism” – the notion, in this context, that “the astonishing properties of living matter could ultimately be explained solely in terms of the physics of atoms and molecules”.

I do not feel well-equipped to give an opinion on whether these two positions are correct or not, but they are compelling:

The reductionist argument is undeniably powerful, but it rests on a major assumption about the nature of physical law. The way the laws of physics are currently conceived leads to a stratification of physical systems with the laws of physics at the bottom conceptual level and emergent laws stacked above them. There is no coupling between levels. When it comes to living systems, this stratification is a poor fit because, in biology, there often is coupling between levels, between processes on many scales of size and complexity: causation can be both bottom-up (from genes to organisms) and top-down (from organisms to genes). To bring life within the scope of physical law – and to provide a sound basis for the reality of information as a fundamental entity in its own right – requires a radical reappraisal of the nature of physical law, as I am arguing.

(Emphasis mine)

There’s an old XKCD comic that “biology is just applied chemistry; chemistry is just applied physics”. Davies argues against this: there is information on each layer. These layers interact in interesting and notable ways. They are not merely layers of abstraction of systems, but rather there is something going on at each layer which can not be reduced to just the “base” most layer.

5. Quantum Weirdness

The book spends two fascinating chapters on the interaction between the preceding ideas and quantum physics. My review is already getting long, so I will limit my discussion here to one fascinating examples of quantum mechanics showing up in biology:

The bird’s retina is packed with organic molecules; researchers have zeroed in on retinal proteins dubbed ‘cryptochromes’ to do the job I am describing. When a cryptochrome electron is ejected by a photon, it doesn’t cut all its links with the molecule it used to call home. … The electron, though ejected from its atomic nest, can still be entangled with a second electron left behind in the protein atom, but, because of their different magnetic environments, the two electrons’ gyrations get out of kilter with each other. … According to the theory of the avian compass, these particular free radicals react either with each other (by recombining), or with other molecules in the retina, to form neurotransmitters, which then signal the bird’s brain. This neuro-transmission reaction rate will vary according to the specifics of the spooky link and its mismatched gyrations of the two electrons, which is a direct function of the angle between the Earth’s magnetic field and the cryptochrome molecules. … Is there any evidence to support this spooky-entanglement story? Indeed there is. … The era of quantum ornithology has arrived!

Davies gives several other interesting examples of quantum biological effects – such as the role in photosynthesis and smell. However, he is also ready to admit that the early quantum biological evidence “have been hotly debated” and that some “early claims were overblown”. Aside from the particular anecdotes, the part of this section that stuck with me was how interesting it is that there is sufficient evolutionary selection pressure for quantum biological effects to have arisen.

6. Conclusion

I came away from Demon in the Machine with a few things that stuck. First, the Maxwell’s demon paradox has actually been “solved”. The resolution through Landauer’s principle – that information erasure, not measurement, costs energy– feels like one of those insights that I’m surprised I hadn’t encountered before. Second, information engines are in-principle buildable things, and that there is suggestive evidence that biological systems operate by similar mechanisms. Third, Davies’ argument in favor of “top-down causality” is an interesting challenge to the common reductionist frame for physics and other hard sciences.

I’d strongly recommend Demon in the Machine; it was quite thought-provoking.

-

Or if I had, it wasn’t in a way that at all stuck to the same extent it did after I read Davies’ book ↩︎