In the end, we self-perceiving, self-inventing, locked-in mirages are little miracles of self-reference. … Our very nature is such as to prevent us from fully understanding its very nature. – Douglas R. Hofstadter

Most people know of Douglas Hofstadter for his masterpiece Gödel, Escher, Bach (“GEB”). I quite enjoyed GEB, but one of his lesser known books – I Am a Strange Loop – has stuck with me in a more profound way than GEB. In looking at other reviews of Strange Loop, I saw the common criticism that it’s the “easier, more approachable” version of GEB. Admittedly, GEB is a doorstop to read through; it has sections written in dialogs, makes heavy use of metaphor, and so on. GEB is a triumph of conveying a certain set of ideas: Gödel incompleteness, Turing completeness, and self-referential systems, among others. But Strange Loop stands on its own as an excellent philosophical book.

I Am a Strange Loop goes much deeper into one of the topics that is discussed in a cursory way in GEB: what are “souls”, what is “I”, and how do we get meaning from meaningless physical constituents. If this sounds like metaphysics, that’s intentional. Strange Loop discusses in depth philosophy of mind, the ontological status of the “self”, and “downward causality”.

1. Strange Loops

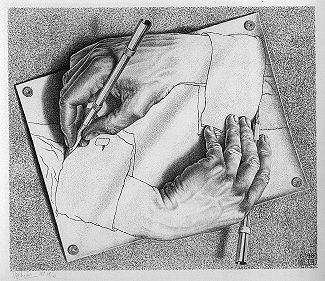

Hofstadter coins the term “Strange Loop” to point to a particular phenomena that occurs within certain hierarchical systems. Two famous examples of strange loops are M.C. Escher’s Drawing Hands, in which two hands appear to be drawing each other, and Kurt Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, which use self-reference to prove that, loosely, formal mathematical systems of sufficient power cannot be both complete and consistent.

A “strange loop” occurs when a hierarchical system has no clear top or bottom – rather, the hierarchy appears to loop back on itself into a cycle. In Escher’s hands, there is no “top hand” drawing the “bottom hand”, and yet there still is the hierarchical relationship of hand one draws hand two, which draws hand one, which draws hand two, and so on. Hofstadter refers to this quality as a “tangled hierarchy”.

Not all tangled hierarchies are strange loops in Hofstadter’s sense, though. The “strangeness” of a “strange loop” comes from when a system is able to perform self-reference. That is, a system that can point to itself in statements it makes. This is where you get fun paradoxes like the Liar’s Paradox: “This statement is false”. Self-reference also forms the basis for Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. I will not try to explain Gödel incompleteness here (though I’d highly suggest either GEB or Gödel’s Proof), but the rough shape is encoding something like a Liar’s paradox within a mathematical proof using a special form of number theory.

Hofstadter goes on to argue that the concept of “I” and consciousness itself are strange loops.

2. The “I” Symbol

Where is the strange loop in the brain? Hofstadter begins with the physical: a brain is a system of neurons that supports representations of a system of symbols. A symbol, in its simplest form, is just a pattern. These symbols often correspond to things out in the world – “dog”, “hot”, “table”. Simple creatures only need a small set of symbols; more complex creatures evolve the use and representation of a greater number and complexity of symbols. The strange loop arises when the system begins to have a symbol for itself – the “I” symbol.

Among the untold thousands of symbols in the repertoire of a normal human being, there are some that are far more frequent and dominant than others, and one of them is given, somewhat arbitrarily, the name ‘I’

Similar to how the symbol for “dog” or “hot” or “table” is created through some mixture of perception reinforcement and innate genetic programming, so too is the symbol for “I”. Self-reference is a quite useful symbol to have. It allows you to reason about your state within your environment in a rich way. Hofstadter continues that, though useful, the “I” symbol is still just a symbol:

Because of the locking-in of the ‘I’-symbol that inevitably takes place over years and years in the feedback loop of human self-perception, causality gets turned around and ‘I’ seems to be in the driver’s seat.

The strong reinforcement of the “I”, particularly through interpersonal relationships and culture, results in the “I” symbol being locked in to a seemingly privileged position of appearing primary to other symbols. There is this perception that there is an “I” driving the body around, it is the “I” perceiving things from the seat of the brain, and it is the “I” symbol itself that is making decisions. Strange Loop argues that this is not a true reflection of reality, but is instead a “hallucination”:

My claim that an ‘I’ is a hallucination perceived by a hallucination is somewhat like the heliocentric viewpoint… The basic idea is that the dance of symbols in a brain is itself perceived by symbols, and that step extends the dance, and so round and round it goes.

The “I” symbol is notable because it is both conceived of as observer and observed. Many thought patterns have this self-referential mode: I can think the thought “I am thinking this thought”. But this loops back on itself in strange loop fashion – the “I” observing the thought and the “I” referenced in the thought itself are akin to Escher’s self-drawing hands.

This is why Hofstadter calls this a “hallucination perceived by a hallucination”. Hofstadter compares this shift to the Copernican revolution, changing from an Earth-centric geocentric model to the Sun-centric heliocentric model – which is a more “accurate” model of physical reality. The analogically geocentric model of thought is the conventional model: “I am a self, I think thoughts”. The analogically heliocentric model is: the brain is a symbol processing machine, of which “I” is a particularly powerful symbol. However, “I” is not ontologically distinct from any other symbol in the brain; it does not exist in a “prior” or privileged position. The “I” symbol is real, but it does not imply the causal structure that we intuitively feel – that the “I” is what is choosing to act, or is what is perceiving.

The obvious followup question to this is, if the “I” doesn’t have causal power over what we decide to do, then what is making decisions? Hofstadter’s answer is what he refers to as “downward causality”.

3. Downward Causality

Strange Loop distinguishes two types of causality: “upward causality”, and “downward causality”.

Upward causality is what we conventional think of as reductionist causality: reducing a problem to its simplest parts helps us understand causal relationships. Diseases are best understood in terms of the bacteria or viruses that cause them; in turn, those bacteria are best understood via their genetic components; genetic interactions are mediated by specific proteins; proteins have a particular chemical structure that are affected by various atomic-scale forces; these atomic forces are carried by force-carrying particles… and so on. The causal forces push upward: the atomic forces influence the proteins, influence the bacteria, influence the disease progression.

Downward causality is the reverse of this: the “top down” reasons for an occurrence have just as much causal power. A disease spreads because of improper public health facilities, or poor social acceptance of hand washing. Failing to wash one’s hands does have causally explanatory power over getting a disease or not, just as the makeup of a bacteria has causally explanatory power of how a human can be infected by that bacteria.

Deep understanding of causality sometimes requires the understanding of very large patterns and their abstract relationships and interactions, not just the understanding of microscopic objects interacting in microscopic time intervals.

It would be, in some sense, an easier task to understand the world if all we had to do was reduce everything to the smallest microscopic objects, and build causality up from there. Hofstadter argues that view is mistaken.

Returning to “I”, this same causality flip is what makes it seem like the “I” is doing some causally important work:

Since we perceive not particles interacting but macroscopic patterns in which certain things push other things around with a blurry causality, and since the Grand Pusher in and of our bodies is our “I”, and since our bodies push the rest of the world around, we are left with no choice but to conclude that the “I” is where the causality buck stops. The “I” seems to each of us to be the root of all our actions, all our decisions.

So where does this leave us? The “I” has causal power, but not in the way we intuitively think. If I stand up to get a glass of water, it may not be my internal “I” symbol making the decision, but the causality still runs through the high level pattern of “I”-ness. “I am thirsty” has explanatory power over my decision.

4. “Will” and “Free Will”

Which then brings us to the hobby horse of any philosophy of mind discussion: free will. Hofstadter plainly argues that “free will is an illusion”, similar to how the “I” concept is a hallucination. However, Hofstadter claims that not much is actually lost in this resignation over free will:

I am pleased to have a will, or at least I’m pleased to have one when it is not too terribly frustrated by the hedge maze I am constrained by, but I don’t know what it would feel like if my will were free. What on earth would that mean? That I didn’t follow my will sometimes? … I guess that if I wanted to frustrate myself, I might make such a choice — but then it would be because I wanted to frustrate myself… in either case, my non-free will would win out and I’d follow the dominant desire in my brain.

One of the best litmus tests for discussion of free will that I’ve collected is the notion that a free will “could have chosen otherwise” – that is, were you in the same position, it is conceivable that a different decision would have been made. Hofstadter argues that this notion of “could have chosen otherwise” is part of the illusion of the “I”. The “I” allows us to feel like we’re a party to our decisions, but that is merely a feeling:

Our will, quite the opposite of being free, is steady and stable, like an inner gyroscope, and it is the stability and constancy of our non-free will that makes me me and you you, and that also keeps me me and you you.

I find this to be a rather tidy resolution of the question of free will. While this discussion is admittedly still in the abstract, it does appear that this explanation would give a way to ground the “feeling” of free will with a symbolic and computational model of cognition. This reconciles a fundamentally materialist view of cognition with the feeling of “spooky ability to chose otherwise”.

5. Distributed Selves

I would be remiss if I didn’t get in a mention to two of the most emotionally impacting chapters of Strange Loop, wherein Hofstadter discusses the death of his wife. One of the interesting implications of Strange Loop’s symbolic interpretation of consciousness is that these symbols can be transmitted – imperfectly, but partially transmitted nonetheless. This has implications for how we interact with others, as our interactions result in corresponding symbols of their “I” or “Self” being transferred:

One day, as I gazed at a photograph of Carol taken a couple of months before her death, I looked at her face and I looked so deeply that I felt I was behind her eyes, and all at once, I found myself saying, as tears flowed, ‘That’s me! That’s me!’ … I realized then that although Carol had died, that core piece of her had not died at all, but that it lived on very determinedly in my brain.

We live inside such people, and they live inside us… someone that close to us is represented on our screen by a second infinite corridor, in addition to our own infinite corridor. We can peer all the way down — their strange loop, their personal gemma, is incorporated inside us.

Dispassionately, I’m not sure how much credence to give to this notion, but it is a beautiful idea. It does seem more than reasonable that we represent others with increasingly rich inner symbols the longer we’ve known them, and it seems evident that those systems can, and indeed do, persist after the death of the symbol’s person.

6. Conclusion

I first read Strange Loop several years ago, during a time of significant personal change. Many of the ideas it expounds have become surprisingly load-bearing over the subsequent years. Strange Loop gave me an intellectually satisfying “in” to exploring my own mental landscape with both curiosity and humility, made me much more uncertain and curious about what is going on inside LLMs, and left me with a great appreciation for Hofstadter as both a thinker and a writer. If any of the ideas above resonated, I’d highly recommend I Am a Strange Loop.