How does a distributed system reliably determine when one of its members has failed? This is a tricky problem: you need to deal with unreliably networks, the fact that nodes can crash at arbitrary times, and you need to do so in a way that can scale to thousands of noes. This is the role of a failure detection system, and is one of the most foundational parts of many distributed systems.

There are many rather simple ways to solve this problem, but one of the most elegant solutions to distributed failure detection is an algorithm that I first encountered in undergraduate Computer Science: the SWIM Protocol.1 SWIM here stands for “Scalable Weakly Consistent Infection-style Process Group Membership”.

What is a Failure Detector

SWIM solves the problem of distributed failure detection. Lets sketch out this problem with a bit more detail. Suppose you have a dynamic pool of servers (or “processes” as they’re often called in distributed algorithms). Processes will enter the pool as they’re turned on, and leave the pool as they are turned off, crash, or when they become inaccessible from the network. The problem statement is that we want to be able to detect when any one of these servers goes offline.

The uses for such failure detection systems abound. Things like: determining node failures on workload schedulers like Kubernetes, maintaining membership list for peer-to-peer protocols, and determining if a replica has failed in a distributed database like Cassandra.

As a toy example, let’s pick something concrete: let’s say we’re building a distributed key-value store. We’re just getting started with our KV-store. For today just need to set up the membership system, wherein distributed replicas of the data can discover each other. Each replica needs to know of the existence of all the other replicas, so they can run more complicated distributed systems protocols – things like consensus, leader election, distributed locking, etc. All those other algorithms are fun, but we first need the handshake of “who am I talking to?” and “I need to know when one of my peers fails”. That’s failure detection.

What properties do we want for our failure detector?

- If a server fails, we should know about it within some bounded time. This is Detection Time

- Faster detection time is preferable.

- If a process doesn’t die, we shouldn’t mark it as dead. If we relax this to allow for “false positives”, we ideally want a quite low False Positive Rate.

- The amount of load on each node should scale sublinearly with the number of nodes in the pool. That is, ideally the amount of work per node is the same whether we have 100 nodes or 1,000,000 nodes.

What properties do we assume about nodes and the network?

- The network can drop packets or become partitioned.

- Nodes can crash at arbitrary times during program execution. We cannot rely on nodes doing anything (like sending an “I’m crashing” message) just prior to crashing, for example.

- All nodes can send network packets to all other nodes.

- Packets on the network have propagation time.

Reasoning up to Failure Detectors

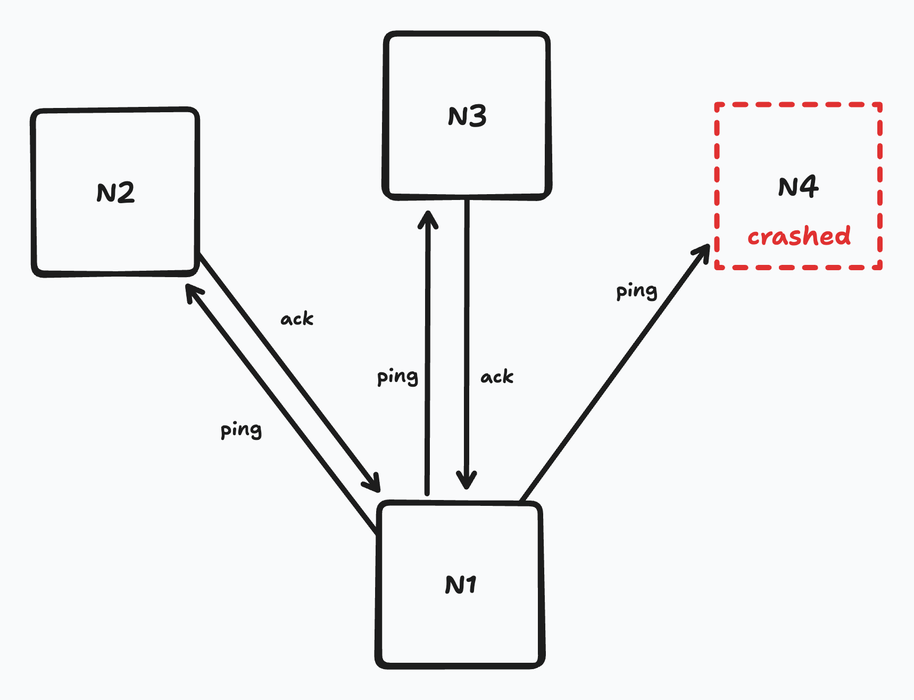

What is the most naive functional failure detector that we could build? Well, for some node $N_1$ in a node pool of ${ N_1, N_2, …, N_{10} }$, $N_1$ could ping each of nodes ${ N_2, …, N_{10} }$. Each of those pinged nodes could send an acknowledgment of the ping, as soon as the ping was received. When $N_1$ receives a ping from, say, $N_4$, then $N_1$ knows that $N_2$ is still “alive”.

Ping and acknowledgment

Looking at this figure, if $N_1$ waits for some chunk of time, maybe retries a few times, but still never hears back from, say, $N_4$, then it can mark $N_4$ as “dead”.

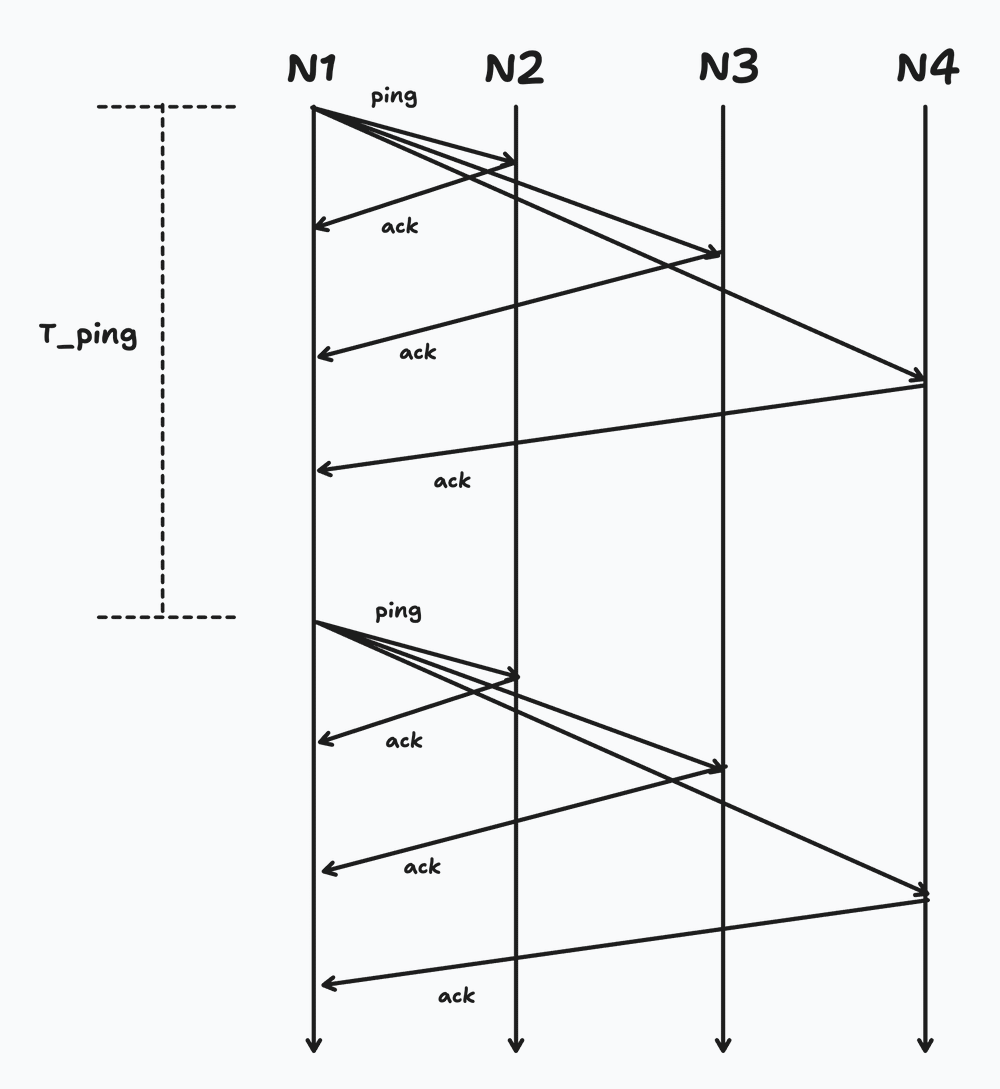

Every time we hear a ping back from another node, we know it’s alive “now”. But we need to know the state of all members over time, so we run this procedure in sequence many times. We can call the time between each ping we send out as $T_{ping}$. And we can call the time we wait to hear back as $T_{fail}$. Both of these become tunable parameters in our system. If we increase $T_{fail}$, we decrease the chance that we accidentally mark a neighbor as “dead” due to e.g. a transient network blip. But if we increase it too long, then we would also allow an actually dead node to still sit in our membership list for a long time – which we don’t want either.

Time between pings

Generalizing this, each of ${ N_1, N_2, …, N_{10} }$ all independently run this ping approach. Finally, to bootstrap the process, we can hardcode all the member node IPs in at startup. If a node crashes but later comes back online, it can broadcast a ping to each of its peers, who then mark it as “alive” and start pinging it regularly again.

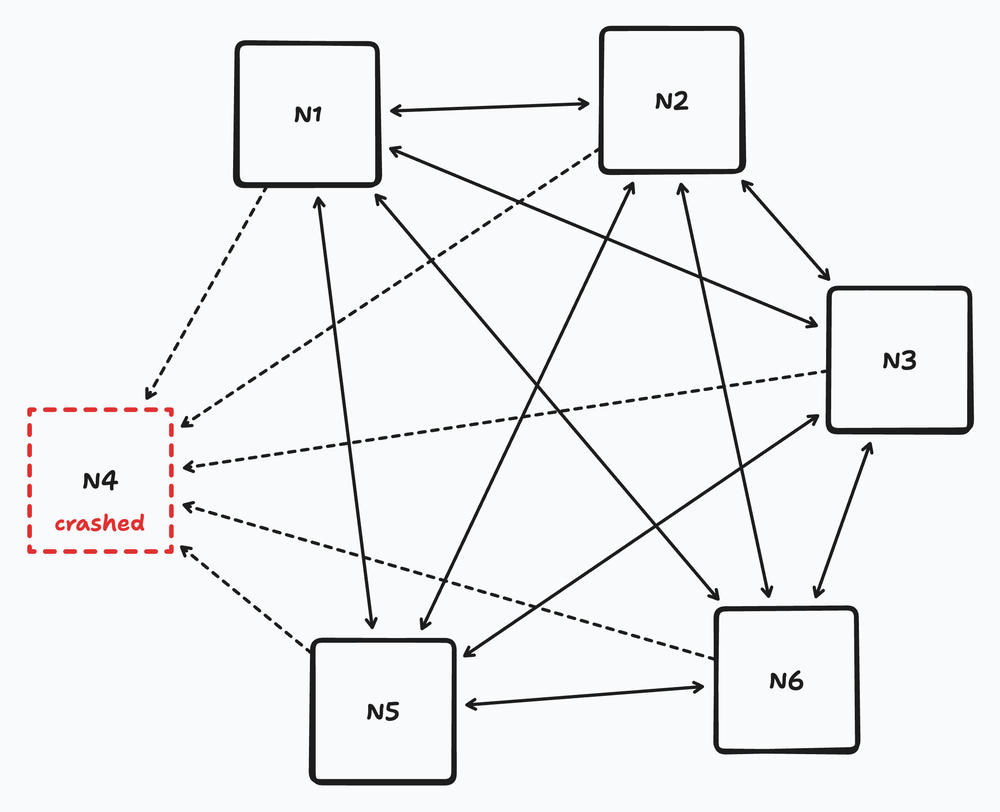

All-to-all heartbeating

Woohoo, we’ve just invented a basic form of heartbeating!

What are the characteristics of our basic system?

- Number of messages: $k$ per $T_{ping}$ seconds, for each node, where $k$ is the number of nodes in our pool

- Time to first detection: $T_{fail}$.

What about accuracy? Well… since we allow for an unreliable network, it’s sadly provably impossible to have both completeness (all failures detected) and accuracy (no false positives). See this paper if you’re curious. In a perfect network with no packet loss, we would have strong accuracy, however.

Time to SWIM

Surely we can do better than “the most naive thing we could think of”. This is where SWIM comes in.

SWIM combines two insights: first, that all-to-all heartbeating like our first example results in a LOT of overlapping communication. If nodes were able to “share” the information they gathered more effectively, we could cut down on the number of messages sent. Second, network partitions often only affect parts of a network. Just because $N_1$ can talk to $N_2$ but can’t talk to $N_3$, this doesn’t necessarily mean that $N_2$ can’t talk to $N_3$.

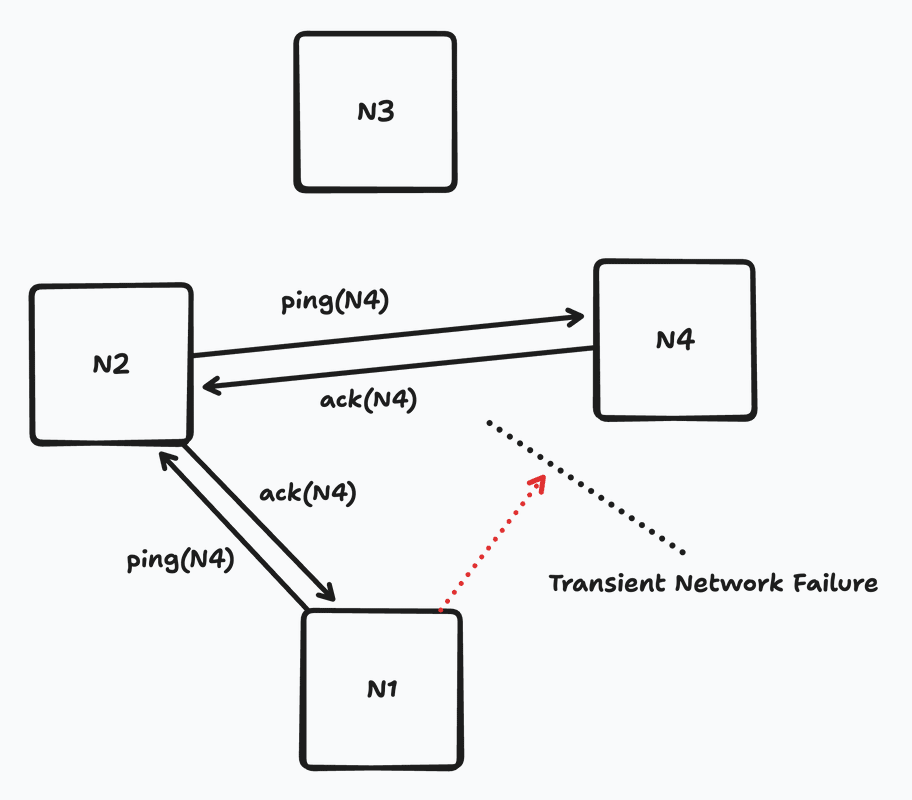

The tagline for SWIM is “outsourced heartbeats”, and it works like this:

- Similar to all-to-all heartbeating, each node maintains its own membership list of all the other nodes it’s aware of. In addition to this list, each node also keeps track of a “last heard from” timestamp for each of the known members.

- Every $T_{ping}$ seconds, each node ($N_1$) sends a ping to one other randomly selected node in its membership list ($N_{other}$). If $N_1$ receives a response from $N_{other}$, then $N_1$ updates its “last heard from” timestamp of $N_{other}$ to be the current time.

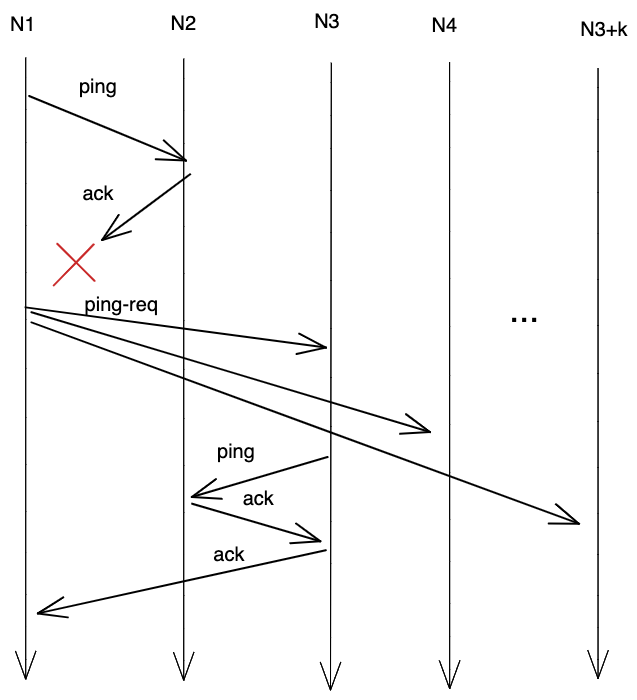

- Here’s the outsourced heartbeating piece: If $N_1$ does not hear from $N_{other}$, then $N_1$ contacts $j$ other randomly selected nodes on its membership list and requests that they ping $N_{other}$. If any of those other nodes are able to successfully contact $N_{other}$, then they inform $N_1$ and both parties update their “last heard from” time for $N_{other}$.

Outsourced heartbeating

- If after $T_{fail}$ seconds, $N_1$ still hasn’t heard from $N_{other}$, then $N_1$ marks $N_{other}$ as failed.

At this point, $N_1$ has determined that $N_{other}$ has failed. To make the whole process happen more rapidly, $N_1$ includes this information to the rest of the network, usually by including information about $N_{other}$’s failure in its ping messages to neighbors, which then gradually propagates through the entire network gossip style.

SWIM protocolSource

What are the characteristics of this more sophisticated failure detector?

- Number of messages per node per interval: $1$ ping in the common case. At most $1 + j$ when outsourcing is triggered (where $j$ is the number of “outsourced” ping requests).

- Time to first detection: It takes some fancy math to get to this point, but in expectation this is $\frac{e}{e-1} * T_{ping}$

What’s notable about these two properties is that: First, the number of messages we send no longer scales with the size of the pool. We could have 1M or 10M or 100M nodes and still send the same number of messages. Second, the expected time to first detection also is still independent of the number of nodes. It’s a constant, tunable by the $T_{ping}$ interval.

Why Did SWIM Stick With Me

So that’s the trick. It’s quite simple! Just outsource some of our detection to you neighbors. What made SWIM stick with me is that it is clever. It seems to legitimately require some inspiration to get to this solution. We could try to build up other approaches on top of all-to-all heartbeating, but most of the obvious improvements aren’t competitive with SWIM. For example:

- Subset heartbeating, where you pick a subset of your membership list and only ping those. This reduces the number of messages you need to send, but increases the time to detection significantly.

- Centralized heartbeating, where you elect one node as a leader and it’s the only one that sends the pings and has authority over the membership list. This also reduces the number of total network messages, but puts undue load on a single node.

- Basic Gossip Propagation, which looks like “SWIM without the outsourced heartbeats”. Health information is piggy-backed on ping packets, but you only ever rely on your own direct pings. This also has reduced network messages and bounded per-node load, but takes $O(\log(N))$ ping intervals to propagate through the whole network – not constant like SWIM gives you.

All of these have tradeoffs that SWIM exceeds. SWIM is simple, elegant, solves a challenging problem, and felt to me like “algorithm design has something interesting to say about distributed systems”. That’s ultimately why it’s stuck with me since I learned of it.

Further Reading

- SWIM in practice:

- CS425 slides on Failure Detectors and Membership lists