I recently encountered a fun performance problem. Consider the following:

- You need to distribute a key-value dataset with string keys and opaque value blobs in the 100B - 1MB range.

- There are on the order of 10k keys to distribute.

- Critically, you are in a constrained memory environment where you do not have enough memory to load all the blobs into memory at one time. You do, however, have enough memory to load all the keys and a small amount of metadata, if you want.

- The key access pattern on the data is random.

- The workload is entirely read-only.

- You get to choose the file format and reader, but you must be able to disseminate this whole structure as one file.

- Due to environment restrictions, you can’t use

mmapto load files into memory.

I’ve heard the good news about SQLite from Simon Willison, Ben Johnson, and others, and thought this might be an interesting use case. I built out both the reader and writer components. TLDR, it worked!

The latency requirements here were rather sensitive as well, so I tried to squeeze all I could out of SQLite in terms of keeping both the memory footprint and read latency low. I diligently read through the SQLite pragmas page, which inspired my WITHOUT ROWID post.1 In the end, the SQLite-based solution worked out quite nicely. 2 However, I had the nagging suspicion that I was overlooking an obvious solution that was simpler than SQLite.

Yes, there are also other key-value stores like RocksDB – but that also felt like something of a heavy dependency for a read-only workload. Yes, I could use something like a line-delineated file, scan through the file for the keys, store the byte offsets, and scan to the offset at read time. Yes, I could make my own small file format that stores the key-value byte offsets in a header section to improve upon the line-delineated version.

Possible solutions to the problem

And yet, surely the generic version of this problem – “I just want a small, low-dependency way to index into blobs with string keys” – must have a simple, elegant solution.

It does: this is just a zip file. lol.

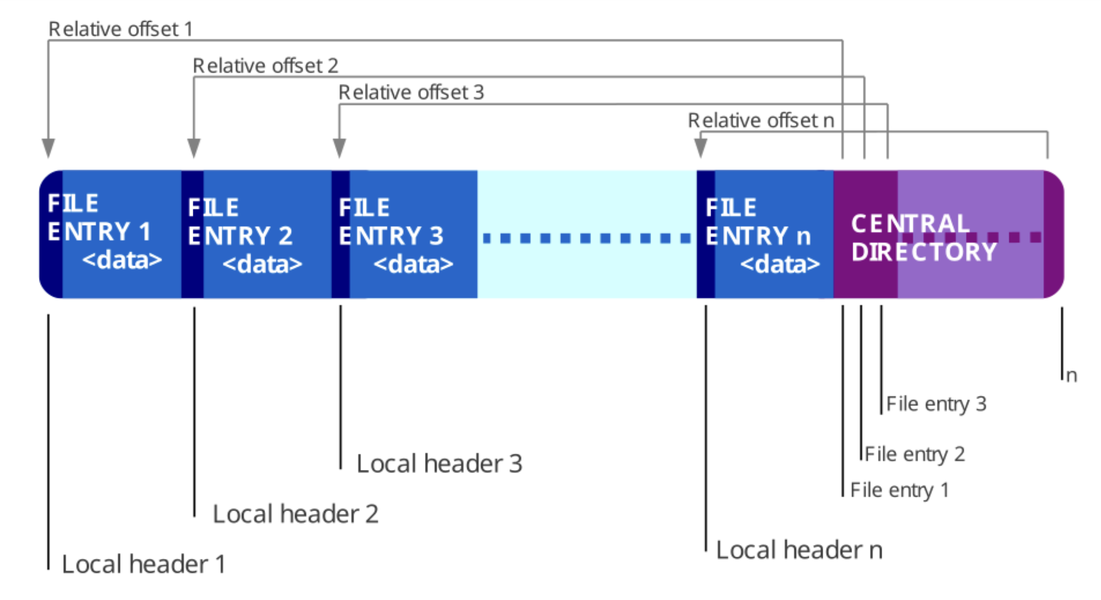

Because the files in a ZIP archive are compressed individually, it is possible to extract them, or add new ones, without applying compression or decompression to the entire archive.

A directory is placed at the end of a ZIP file. This identifies what files are in the ZIP and identifies where in the ZIP that file is located. This allows ZIP readers to load the list of files without reading the entire ZIP archive.

The structure of a ZIP fileSource

Most folks think about .zip files purely in the context of compression, but

zip files don’t actually require the files contained inside to be compressed.

The structure of the zip file is basically exactly what we want. It has a

directory section that is small, contains the list of all the contained files

(keys, in our case), and lets us pull out the data for a key with a random

access pattern. This is in contrast to the other common archive file format,

.tar, which does not have this nice property.

Yes, disks are slow, but if we don’t have any memory to play with… what can we do other than throwing this at the disk? And if we’re going to use the disk anyways, why not pick a format that’s already exactly what we need? Zip has none of the overhead of an execution engine, the B-tree on-disk page layout, and a competent Zip file client exists for any serious programming language under the sun, just like SQLite.

I put together a small benchmark to see if this would work as expected. I

implemented a benchmark matching the constraints above, and tested 4 clients:

SQLite (with and without ROWIDs enabled), Zip file, and a custom .dat file

format which uses a header/offset-pointer approach.

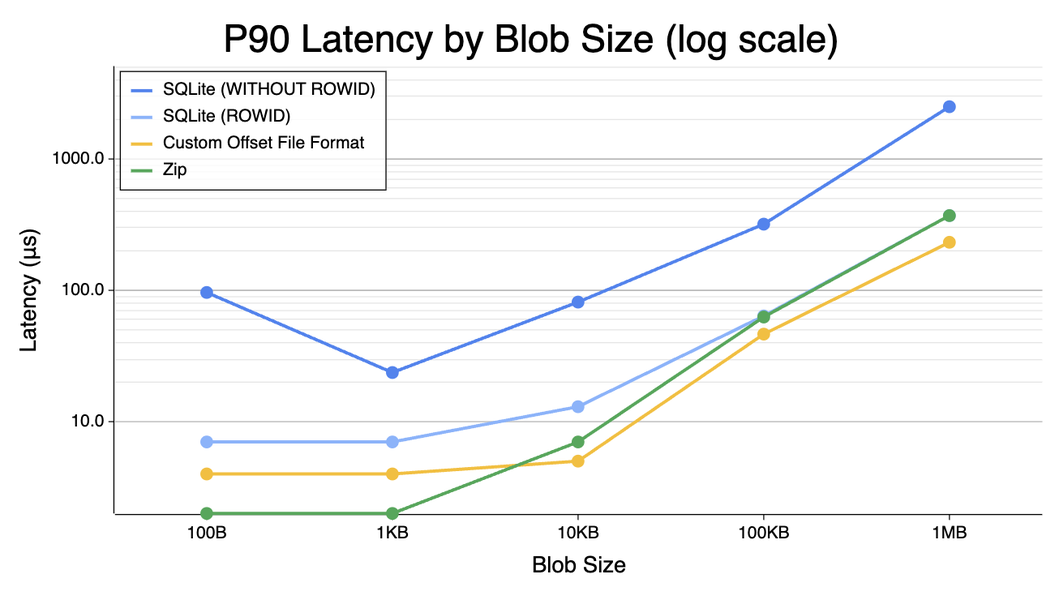

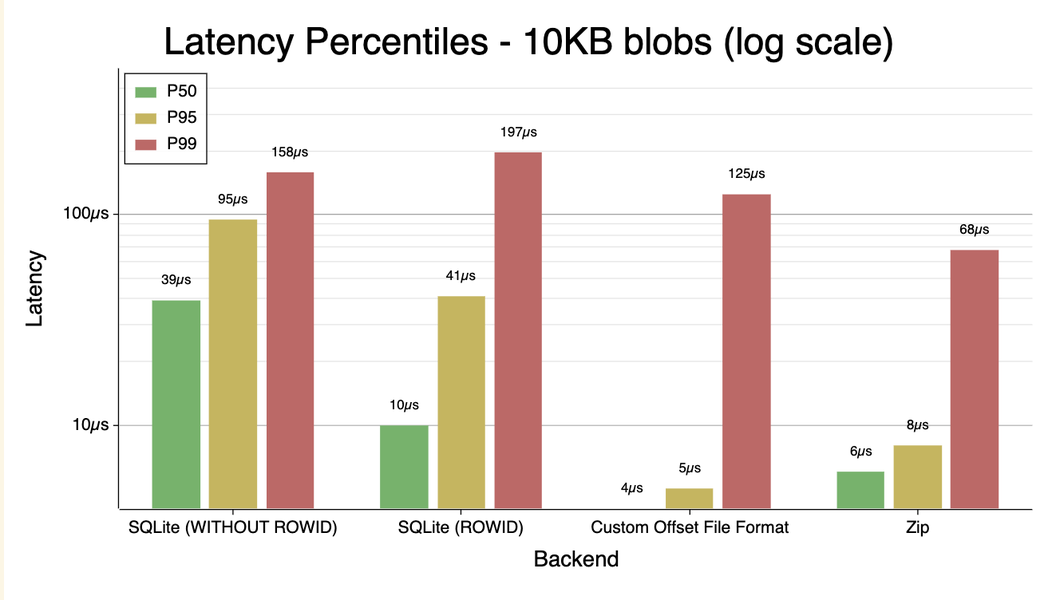

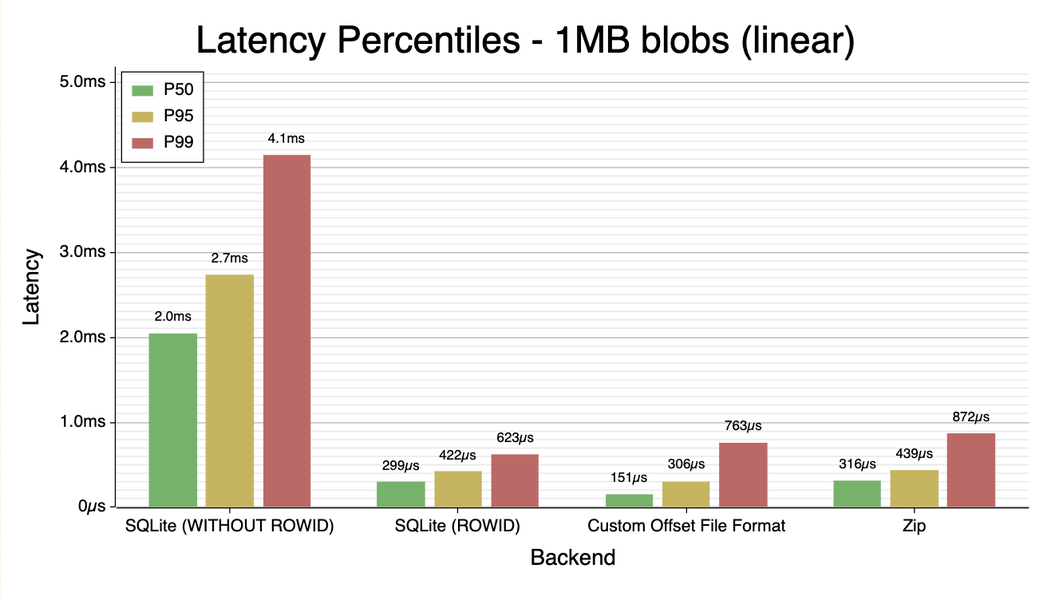

The benchmark produced some interesting results. I’d only treat these charts as directionally correct, but the orders of magnitude and relative positioning of these approaches should be more-or-less correct. Charts (note the y-axis is variably log-scaled or linear-scaled):

P90 latency by blob size 10KB latency percentiles 1MB latency percentiles

- Between 100B and 100KB, the Zip file performs noticeably better than the SQLite. Even with 1MB blobs, where the disk I/O dominates, they perform roughly the same.

WITHOUT ROWIDon the SQLite table made performance significantly worse. This is slightly surprising with the small blobs, but entirely unsurprising past 1KB blob size.- My janky custom file format wasn’t noticeably better in any size range than an off-the-shelf solution, so (expectedly) it makes sense to not DIY an on-disk index like this, at least for my simple use case.

Even though I ended up using SQLite, the humble Zip file is quite competitive as an on-disk index. At least, in this very simple constrained use case.